Nearly six months ago, Pittsburgh’s Fern Hollow Bridge collapsed into Frick Park. The collapse of the bridge, which severed one of Pittsburgh’s most important traffic arteries, drew the nation’s attention to the sorry state of infrastructure around the country. In the wake of the bridge collapse, the urgency of passing legislation to fund improvements to infrastructure was heightened—not least by the President himself, who had already been due to speak in Pittsburgh on the day of the collapse about the importance of infrastructure investment.

When the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law championed by President Biden was passed in November 2021, many breathed a sigh of relief: America’s infrastructure was finally going to be fixed. But this relief, unfortunately, is shortsighted. Our infrastructure problem, particularly regarding automobile infrastructure like highways and road bridges, goes beyond just long maintenance backlogs. The problem is not just that we have too much dilapidated automobile infrastructure. The problem is that we have too much dilapidated infrastructure because we simply have too much car infrastructure.

The Fern Hollow Bridge: A Casualty Of Urban Decline

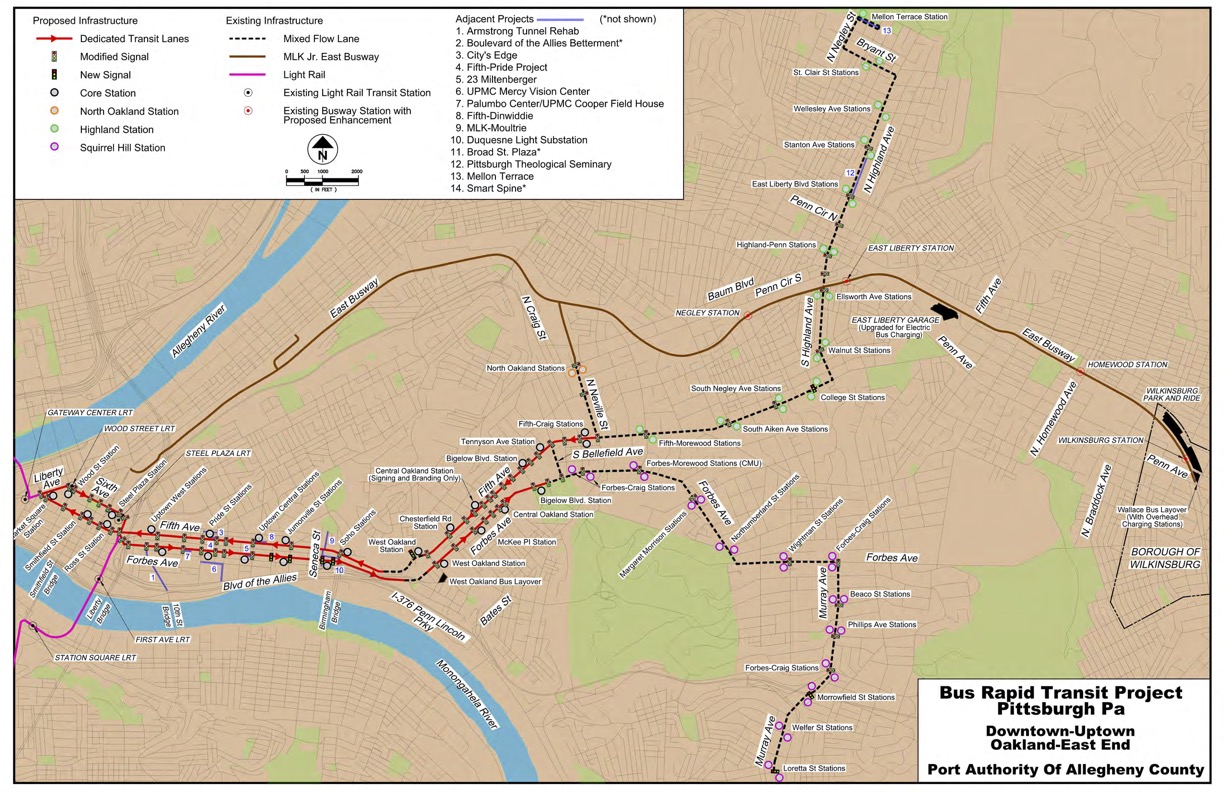

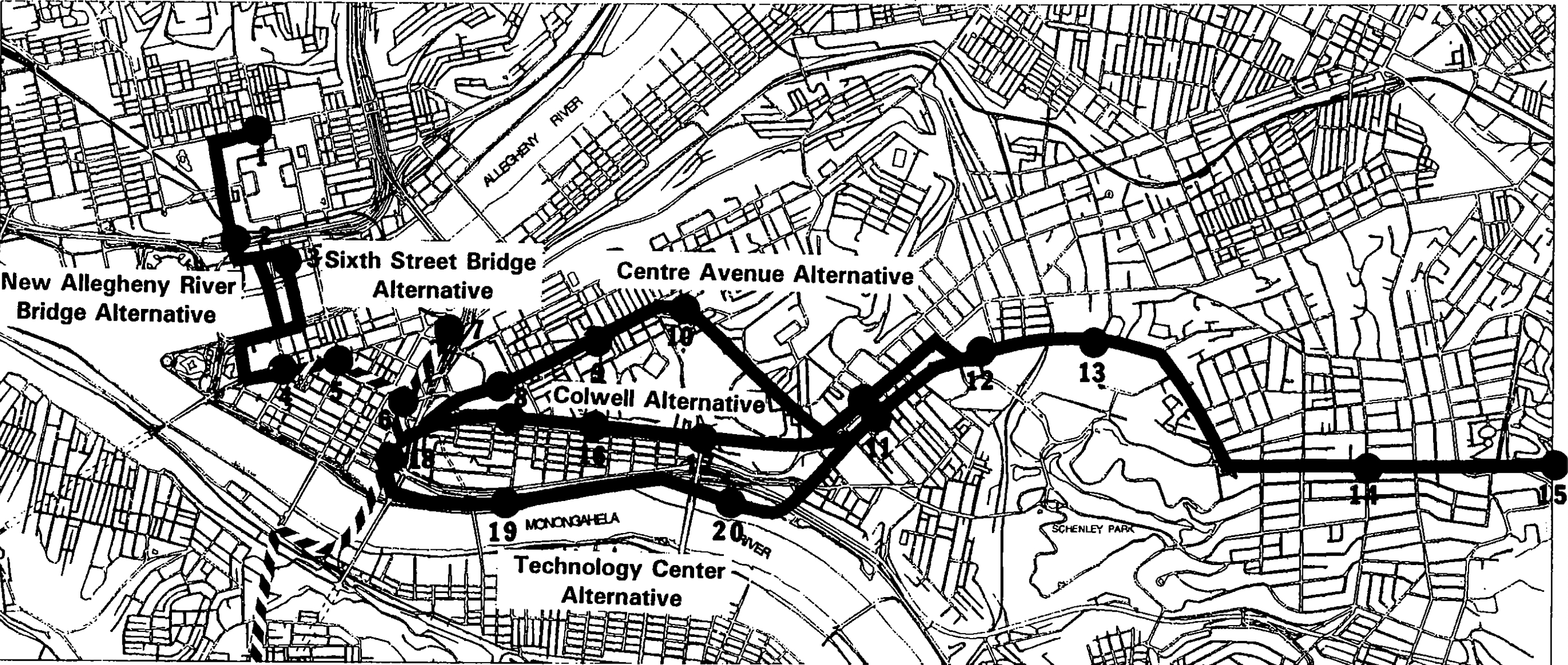

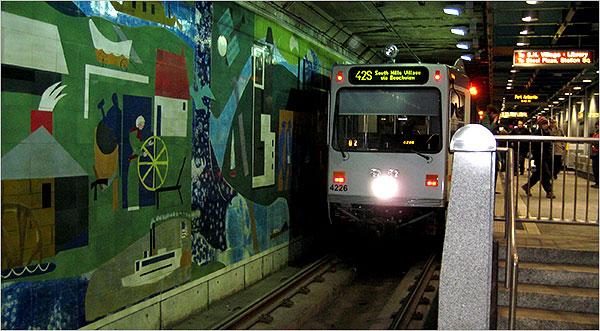

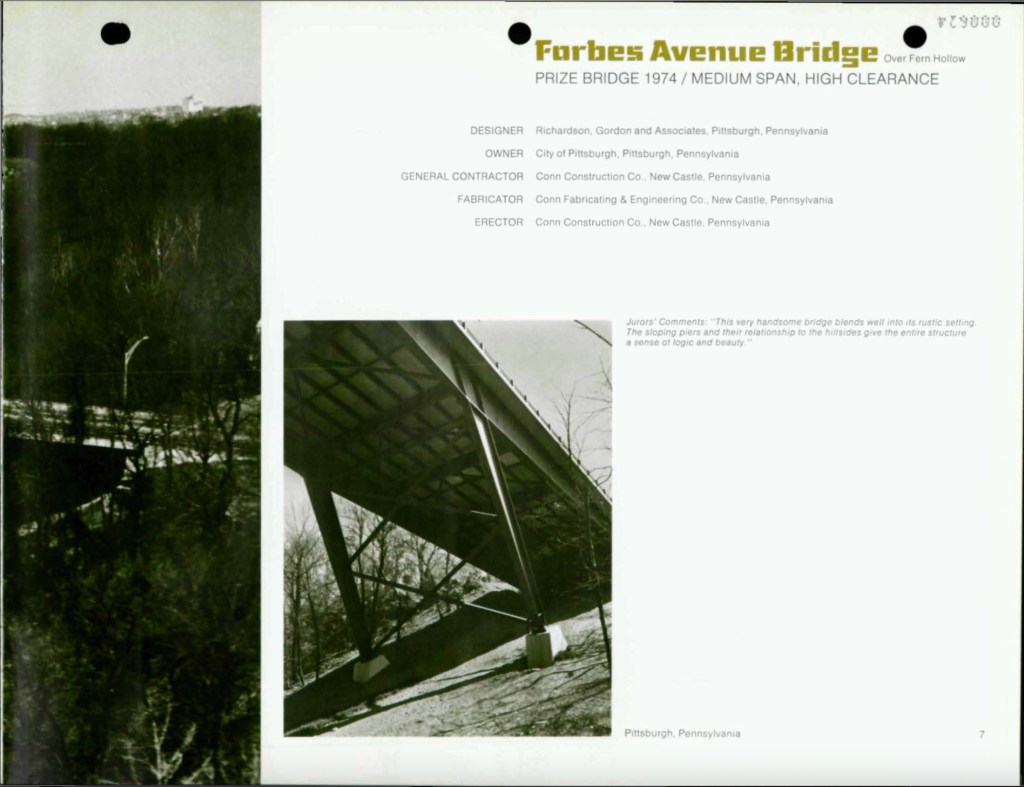

That Pittsburgh was the location of such a high-profile failure of public infrastructure was particularly salient. Pittsburgh is famous for its hundreds of bridges, carrying roads and rails across the region’s steep valleys and ravines. Pittsburgh is also symbolic of the urban decline that has imperiled so much of the nation’s infrastructure. The Fern Hollow Bridge opened in 1973, replacing an older bridge at the same location dating from 1901. The year after its completion, it was named a Prize Bridge by the American Society of Civil Engineers. On a small level, it is symbolic of the optimistic attempts at modernizing the city that were underway in the 1970s. But this decade was the beginning of an incredibly challenging period for the city and region. During the 1970s, the region’s population was in the beginning of a precipitous decline from which it has yet to recover. The 1970 Census was the first one which recorded Allegheny County’s population as lower than the previous Census, and no subsequent Census would record any population growth in the county until the most recent, in 2020.

Glowing praise for the then-new Fern Hollow Bridge from the American Society of Civil Engineers in 1974. (From full booklet here).

The original Fern Hollow Bridge stood from 1901 to 1971 and carried automobiles and streetcars, such as this #67 streetcar exiting the bridge in 1967. (Photo credit: Roger Puta, link)

For the city of Pittsburgh itself, the period of decline had begun before the 1970s. Having already lost 10 percent of its peak population between 1950 and 1960, the city lost another 13 percent between 1960 and 1970, and a staggering 18 percent between 1970 and 1980. Today, the city remains just under half (302,971 recorded in 2020) of its peak population (676,806 recorded in 1950). Pittsburgh’s population decline hasn’t even stopped yet, though it has hopefully been stemmed. (The population loss between 2010 and 2020 was a minimal—perhaps encouraging—0.9 percent). Thanks to suburbanization, Allegheny County has lost a smaller, but still sizable, share of its population since 1970, with 22 percent less population today (1.25 million) than it had in 1970 (1.6 million).

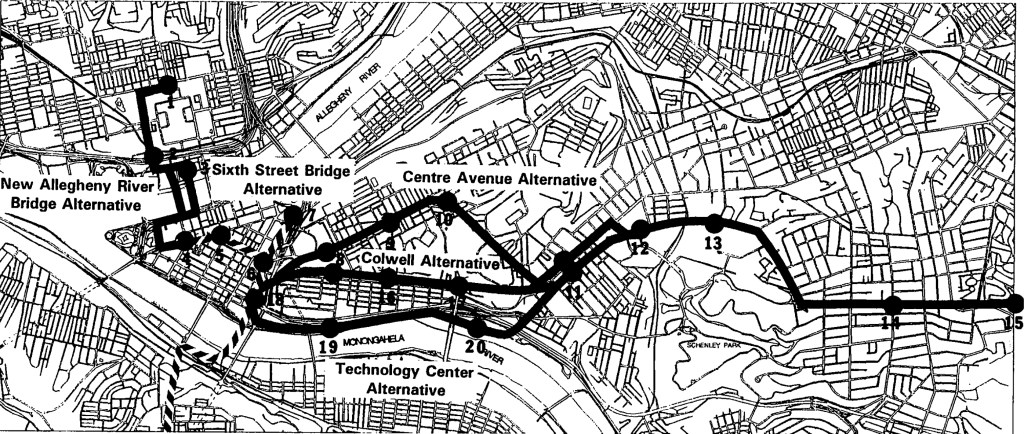

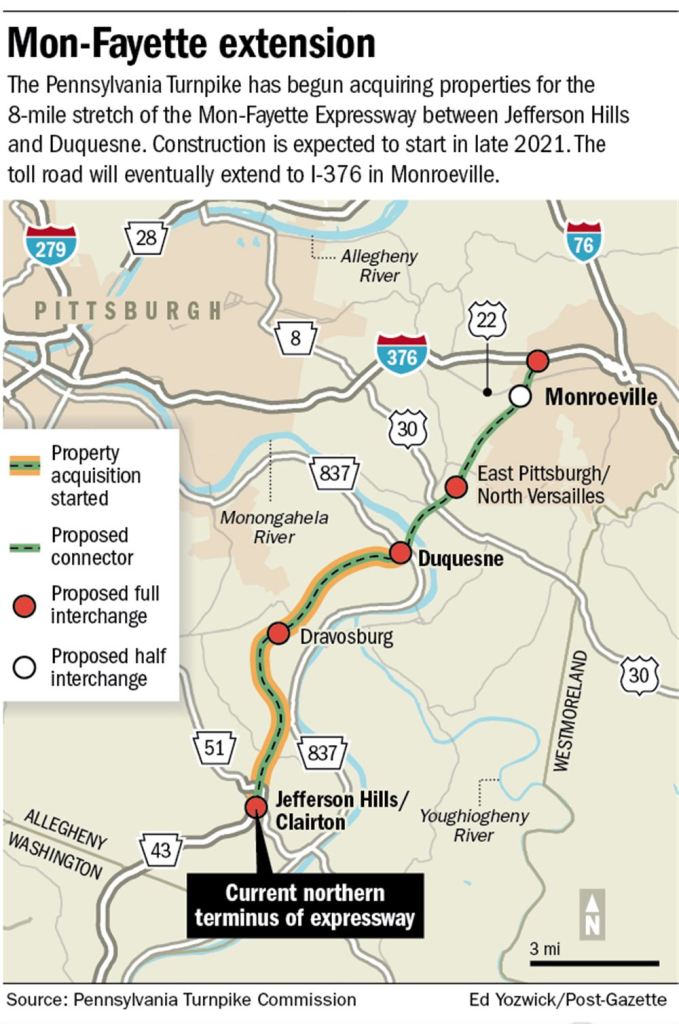

Despite the loss of population, the amount of automobile infrastructure in the region continued to grow. The Downtown-to-North Hills Parkway North opened in 1989, the loop of Interstate 376 to serve Pittsburgh International Airport opened in 1990, and construction on the final section of the Mon-Fayette Expressway is supposed to begin sometime this year. The upshot of this is that the Pittsburgh region has the automobile infrastructure for a region with a much larger population, and a much larger tax base to fund its maintenance. The Pittsburgh region is far from the only one in America that can claim this story. Across the post-industrial cities and towns of the Northeast and Midwest, there are likely many more miles of roadways and bridges than can be supported by those regions’ current populations. If we want to get the condition of our infrastructure under control, we need to start with infrastructure that is appropriately scaled to the regions they serve today.

I am certainly not the first person to make this point—it was pointed out by several on Twitter (and probably others I missed!) in the immediate wake of the Fern Hollow Bridge collapse. What is important to add here is that Pittsburgh already knows exactly how to transform redundant infrastructure for cars into quality mixed-use spaces for people. Several years before the Fern Hollow Bridge collapse, Pittsburgh successfully converted a roadway facing structural issues into a car-free path through one of the city’s largest parks.

The Pocusset Street Transformation

Pocusset Street is a quiet residential street at the edge of the Four Mile Run valley, which separates the northern and southern sections of Squirrel Hill. Until a few years ago, part of the road also connected Squirrel Hill to Greenfield through Schenley Park, serving as a shortcut for the busier roads through the park. (Local cycling advocacy group BikePGH noted that the road’s narrow width and twisty route through the park made it unsafe for pedestrians and cyclists). In 2012, inspections found that the 0.3-mile section of Pocusset Street in Schenley Park, which carries the road on an embankment high above the valley, was not structurally sound. Storm drains were obstructed, and parts of the embankment were washed out, and one part of the roadway was “undermined by a cavity of between 12 and 15 feet.” The problematic section of Pocusset Street was closed to traffic while the city’s Department of Public Works (DPW) considered rebuild options to allow continued car traffic.

The necessary rebuilding work was estimated to cost as much as $700,000, money which the DPW did not have. As an alternative, the city floated a plan to reopen the street for pedestrian and bicycle use only, sparing the cost of a full rebuild while opening a new, safe walking and cycling connection between Squirrel Hill, Greenfield, and Schenley Park. The DPW chose to pursue this plan, setting a first-in-Pittsburgh—and possibly the country, according to BikePGH—example of closing part of a street to car traffic and reopening it for people.

In 2014, Pocusset Street reopened as a car-free roadway. The city resurfaced the road, installed new lighting, painted new demarcations for pedestrians and cyclists (which have faded quite a lot) and, importantly, installed “modal filters” (the fancy term for barriers) at each end to protect users from vehicles. The nature of the street’s route through the park and relatively-narrow width, both large detriments when it carried car traffic, make it very well-suited and pleasant as a mixed-use path. Its connection to the rest of Schenley Park on one end means that residents of Squirrel Hill can access Schenley Park, and others can travel across it, without walking or cycling on the higher-traffic roads in and out of the park. Walking Pocusset Street today, it is difficult to believe that was a shortcut for car traffic not so long ago—I imagine that future car-free streets, despite how important they may seem to traffic today, would quickly feel the same.

Right-sizing Pittsburgh’s Infrastructure

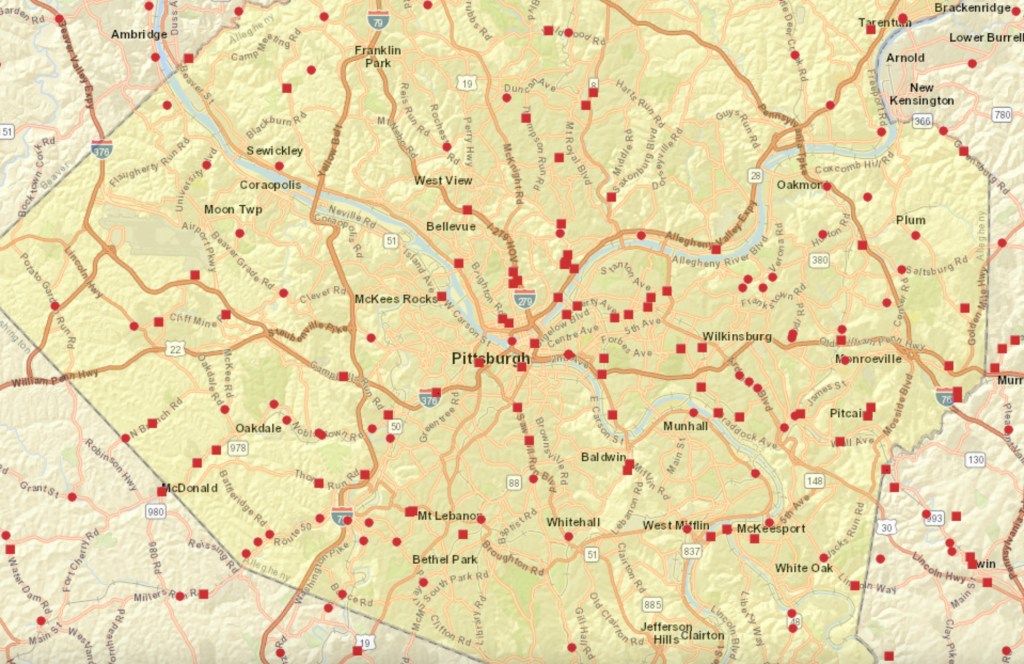

In May, Pittsburgh Mayor Ed Gainey announced the beginning of a “bridge asset management program,” to assess of the condition of city-owned bridges and develop a plan for funding crucial repairs. Across Allegheny County, dozens of bridges are already considered by the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation (PennDOT) to be in “poor condition.” On top of those, Pittsburgh and Allegheny County contain many more miles of roadway and lots more supporting structures, like the embankment carrying Pocusset Street, that are also in need of attention. Suffice to say that the Pittsburgh area’s maintenance backlog is long and expensive, and the kinds of infrastructure issues discovered on Pocusset Street—as well as the high cost for their repair—likely foreshadow the issues that will be unearthed by Mayor Gainey’s new initiative. The Department of Mobility and Infrastructure (DOMI), which took over some of the functions of DPW in 2017, has serious issues with short-staffing and administrative capacity according to recent reporting, adding to the already-large challenge of keeping the city’s decaying infrastructure standing.

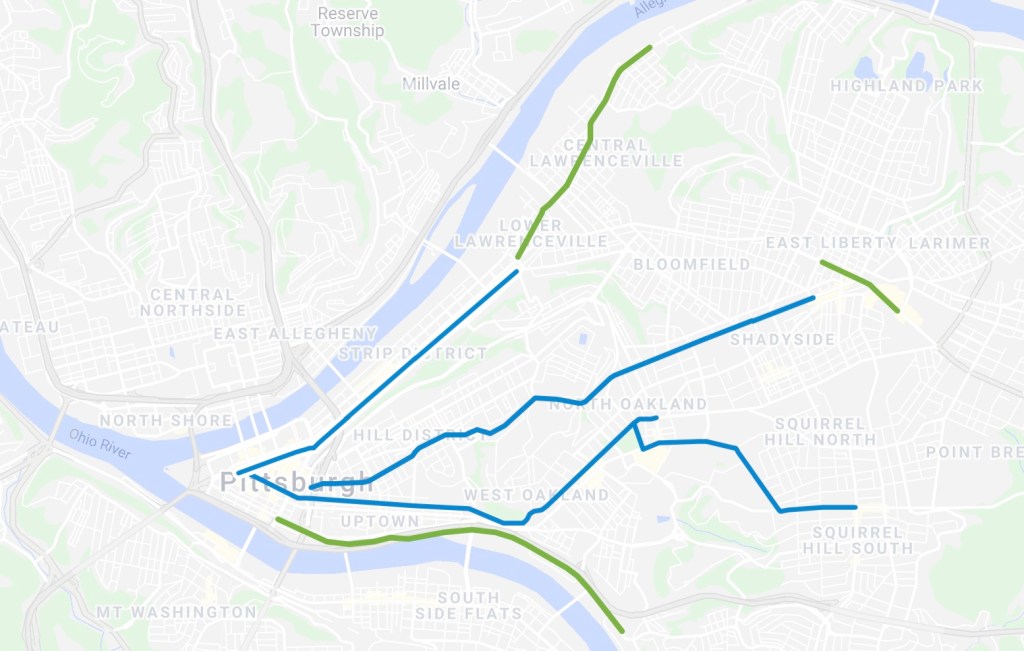

The combination of the high cost of infrastructure renewal and the lack of capacity to carry it out leads to the question of whether rebuilding all of the road infrastructure in need of attention to support current—let alone higher—levels of car traffic is a worthy goal at all. The fact that the Pittsburgh region’s automobile infrastructure is oversized relative to its population should be a compelling enough case for the city government to consider whether its responsibilities in maintaining automobile infrastructure can be scaled back. That is before we come to the imperative for all municipal governments to promote a shift away from automobile journeys wherever possible. In its Climate Action Plan, the Pittsburgh Department of City Planning has set the goal of reducing both transportation-related emissions and vehicle miles traveled in Pittsburgh by 50 percent by 2030. This is an ambitious goal that the city should aim to meet, but for this to be possible, the city must make it safer to get around the city without a car. The best, and proven, way to do this is to provide safe, traffic-free routes for those walking, cycling, or using other mobility devices—not expand capacity for car traffic (which, as we know, will encourage an increase in car journeys).

The car-free transformation of Pocusset Street should serve as a model of how DOMI can use redundant car infrastructure for the benefit of the city. In particular, where sections of road or bridges carry low traffic, have nearby alternatives, or would fit neatly into the planned bike network, the city should convert those to car-free roadways. Doing so across Pittsburgh would be a definitional win-win for the city, which could instead use precious infrastructure funding for more projects—such as improving sidewalks or sewers—and would help Pittsburgh achieve its climate aims. There is every reason to believe that more car-free streets would be popular: events like Pittsburgh OpenStreets prove the demand for more open spaces in the middle of the city, and people should have access to such spaces year-round, instead of for a few days per year.

That said, a car-free conversion will not be the answer to the Fern Hollow problem. The Fern Hollow Bridge will be (and must be) replaced, though ideally, the new bridge will be friendlier to non-motorists than PennDOT’s current proposal. But as the city takes stock of the full extent of its infrastructure problems, it should take the opportunity to stop holding on to a built environment intended for the last century—it should instead reimagine Pittsburgh’s infrastructure so it is built for the city of 2022 and beyond.